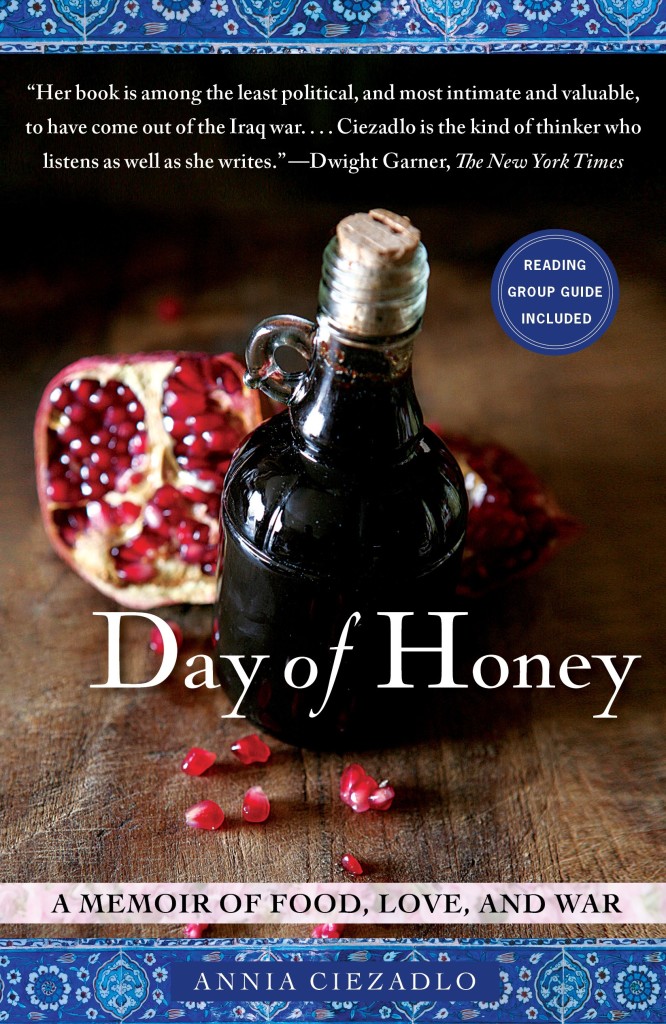

Do you want to know the secret to creating a magical work? After reading Day of Honey it finally dawned on me: The Universe takes a brilliant writer and blesses them with a soul-stirring story that begs to be told.

is not just an award-winning book that has a great story and magnificent writing. It is much more than that. It is a book of record that shows how humans relate to each other through food in times of horrific conflict. Author Annia Ciezadlo is takes us on an unforgettable journey through a Middle East not shown in the media: inside peoples’ kitchens and their hearts.

I learned from her that to be a inspiring writer you have to see the poetry in a quiet bowl of hummus in as much as seeing it in a glowing sunset. You have to be able to find the meaning behind piece of bread that you tear and share. You have to be able to find gratitude in pain. She intermingles poetry with the bloody war, she intermingles history with contemporary scenes in such a way that you feel like you are right there with her at each and every step of the way. As I writer I know how hard it is to do this.

A tiny, tiny excerpt: “A terra-cotta bowl of chicken livers bathed in lemon juice and garlic taxied down onto the table. The others started ordering meze in combinations I’d never imagined, Jabberwocky food, portmanteau creatures from a parallel world: slices of sausage, thick like pepperoni but spicy like chorizo, stewed in sweet pomegranate syrup. Little saucers of hummus with tender spoonfuls of sautéed lamb and pine nuts nestled in their belly buttons. Tiny glasses of crystal-clear arak that clouded into milky iridescence when you added ice. A pickled baby eggplant stuffed with chopped walnuts and hot red peppers and slicked with olive oil” from Day of Honey by Annia Ciezadlo

I am enamored by her work. I am in awe of her spirit. You know after you have a great meal, folks will say, “Ah, I wish to kiss the hands of the chef.” That is how I felt after I finished reading this book. The greatest compliment that I can pay her: Your words will live in my heart forever and will guide my own journey as I try to find my voice. Thank you for that.

Annia’s handling of the prose is delicate; she knows when to play with the words, she knows when to show them respect and in return, they seem to bow to her every command.

If you read one book this year, make it this one. I promise you this: you will never look at food the same way again. It isn’t just a way to fill our stomachs and provide us nutrition. It is the most intimate connection we have to the people around us.

I am so honored that author Annia Ciezadlo agreed to an interview for Life of Spice. Just read the interview and you will know why she has been nominated for every award under the sun and why you should be ordering Day of Honey right now.

Do tell my readers a little about your background. Where did you grow up? Where is home?

I was born in La Grange, Illinois, about an hour outside of Chicago. That’s where I went for summer vacations when I was a kid, to my grandparents’ house, and that’s where I spent every Thanksgiving and Christmas. It’s where my mother lives to this day. That’s the place that I always go back to. But I grew up in Bloomington, Indiana, which was an idyllic place to be a child. Then when I was 13 my mother and I lived in a series of different places, from northern Arizona to the Bay Area, then Kansas City, St. Louis.

Where is home—that’s a little more complicated. In a sense the entire book of Day of Honey is an attempt to answer that question. Some part of me will always feel that Chicago is home, which is funny considering I never even went to school there. Some part of me believes, or wants to believe, that wherever I am at the moment is home.

In your glorious book, you capture history through food. Did you always know you were going to write this book?

Definitely not. I had the idea of writing a food memoir about the Middle East in July 2005. Back then food memoirs were a more obscure genre, not quite the overwhelming juggernaut they are now, and I thought it would be an interesting way to look at a region that is almost always defined solely by conflict. I thought it would be a charming little book about food and the seasons and the countryside, kind of like “A Year in Provence,” but in Beirut. I had this notion that I would not write about conflict, that it would be a paean to everyday civilian life—families sitting around the dinner table, putting up homemade preserves—so that Americans could see that side of the Arab world, the one they almost never get to see.

But once I had the idea it took me two long years to get the proposal out there. I didn’t know anybody who’d pitched a book with a proposal, and I didn’t know how the system worked. That’s why I’m always happy to help writers who are just starting out on the process. As those two years went on, things deteriorated a lot in Lebanon, in ways that began to echo what I had witnessed in Baghdad—what I had been trying to escape from, in a way, with this “Year in Beirut” idea. 2005 was a year of many assassinations in Beirut, and the next few years saw the war between Israel and Hezbollah, and the slowly escalating sectarian violence, and the culmination of all these things is what you see at the end of the book. I started to understand on a much deeper level what my husband and my Lebanese family and my Lebanese friends had been living through for all these years. I realized that this is part of what makes the pleasure of food and family so intense—that it’s not honest to write about people going to the farmer’s market, and eating falafel, without talking about all these other things that they’re dealing with.

In the end, I’m really glad that I didn’t gloss over the conflict. I’m really happy that I wrote about the war as well as the food and the love. But it’s certainly a drastically different book than the one I originally thought I would write. Maybe it’s good that I didn’t know how to write a book proposal and get it out there back in 2005!

I have read your book with great pleasure and just love the way you handle the characters: with a delicate and yet firm hand. Of all the people that you met during your travels, who left the deepest impression on you?

It’s hard to answer that, because for every character that you see in the book, there are a dozen more who I couldn’t include for one reason or another—we didn’t share food, for example. Some of these characters do show up in little cameos, but I could write a whole other book about them. Some of the most memorable people I met as a reporter don’t show up anywhere at all. Like the high school principal who decided to keep his school open even when militiamen from the Mahdi Army told him not to. This guy made a profound impression on me, simply because he was so ordinary: just a little balding, potbellied man with a mustache. I remember he had a miniature potted rosebush in his office. A typical Iraqi bureaucrat. But he was a hero in his ordinary way, a bigger hero than anyone I can think of. He was willing to die to keep his school open! He knew he could die, but he didn’t believe in militias shutting down schools, and he was willing to risk his life for what he believed in, which was education. And there were millions like him all over Iraq. And a lot of them did die. Don’t get me started on the importance of minor characters, or you’ll be sorry. I could go on for hours.

Were you ever afraid of the war? There is so much going on behind your words… the bombs, the sirens… did they scare you or do they end up becoming part of a white noise of sorts?

There was a lot of scary stuff going on. I didn’t even include some of the scariest stuff, like the time an IED exploded outside a mosque just after I’d driven past it. Or interviewing a group of guys who started making not-very-funny jokes about how they were going to kidnap me. I didn’t include those things because I didn’t write this memoir to say, “Hey, look what a badass I am, look at me and my balls of steel.” I hate memoirs like that, and the world has way too many of them. I wanted to keep the focus on the people I knew in Beirut and Baghdad and what they were going through.

Another reason I didn’t include all of that stuff is because for me the stuff I did include was more scary. Seeing our neighbors checking ID cards in the streets of Beirut felt much more terrifying, for me, than almost getting blown up by an IED. There’s a couple of reasons for that, and some of those are particular to me. I tend to be what’s called counter-phobic, which means that if something is scary I’m drawn to it, and don’t feel danger until later, when the rational part of my brain kicks in. Another reason is because I felt that this civil war-type behavior was a danger to my husband, who was the “wrong” religious group for that neighborhood. But I think the main reason is because this was our home, where we lived. And this kind of danger was taking place in a setting that seemed normal, not extraordinary. This wasn’t a war; this was the new normal. That felt much scarier to me, in some ways, than an all-out war. I’m not saying it was more dangerous, mind you; I’m saying that to me it felt more dangerous.

I am curious about your writing process: you have a wonderful way of intermingling an engaging narrative with facts. Would you be willing to give us a sneak peek of the process you use when you write?

I write way too much and try to include everything that ever happened. Also all the cool little tidbits of knowledge that I’ve learned along the way. Then I have to cut a lot. I don’t recommend this process. What I’m trying to work on, and what really helped me finish Day of Honey is learning the art of not saying everything you know. That’s hard to learn but it’s worth it.

In the beginning I had a 700-page book that included a lot of history and politics and background. Almost all of that is gone now, but I like to think their echoes remain throughout the book. My friend Maren Milligan put it beautifully: she reminded me that when you make a stew, you put in a bay leaf, but you don’t actually eat the bay leaf. You take it out, but its flavor remains. I can’t think of a better way to describe the role of research and background in a work of narrative nonfiction.

What advice would you give to your fifteen-year-old self?

When I was a young tomboy, I don’t remember exactly how old, my grandmother took me aside and told me she was going to give me something to “fall back on.” My grandparents were big on this idea that you had to have something to fall back on once your plans for world domination were thwarted. She had gone to secretarial school, and she wanted to teach me typing and shorthand so that I could be a secretary if and when all else failed. She tried to show me how to put my fingers on the keys, how to make each syllable into a dot or a dash.

I got really angry. “I’m not going to be a secretary!” I told her, and I said the word secretary with great scorn, and I stormed out of the room. I wasn’t going to fail. I was going to be an architect, or an astronaut, or a jockey, or a sailor, or whatever it was I wanted to be that week—all of these glamorous and traditionally male-dominated professions that were as far from being a secretary as possible.

Fast forward a decade or two. I’m a journalist, a glamorous and traditionally male-dominated profession. I’m doing a really important interview over the phone. And I’m losing about half of what this person is saying, because my typing sucks, and it turns out it’s really, really hard to take notes by hand when people talk fast. And all I can think is: Wow, that shorthand and touch typing that Grandma tried to teach me would come in really handy right now.

So this is what I would tell my fifteen-year-old self: listen to your Grandma. Respect your Grandma. She can see the future, and she knows where it’s at.

What is your guilty food pleasure?

I never feel guilty for eating. Ever. Wait, that’s not true. Foie gras makes me feel guilty. And I try to avoid eating veal. In general I try to stay away from food products that involve torture and slavery. I get fair trade bananas and I don’t eat much tuna or salmon. I have a complicated relationship to lamb. But Fritos, Cheetos, chocolate, doughnuts, ice cream, and ramen noodles (not the fancy restaurant kind, but the ones that come in a red and yellow package for a dollar)? No guilt.

What advice would you give aspiring writers like me about working on a full length narrative book (scares me!)

I got some excellent advice from my friend Farnaz Fassihi, who wrote a wonderful book about Iraq and Iraqis called Waiting for an Ordinary Day. She taught me to set aside one day a week when you don’t write at all. Just forget about the book for one day. Let the well refill. There were times when I couldn’t do it once a week—maybe once every ten days or two weeks—but it still really helped.

Some day-to-day practical stuff that helps me write: working out, getting some form of intense exercise. Getting up in the morning and not doing anything, anything at all, except writing. When I’m writing I sometimes make a gigantic frittata (quiche, kuku, whatever) at the beginning of the week. Then I just eat that for breakfast all week so I don’t have to stop working to feed myself. And I don’t check email until I’ve written what I’m going to write that day. Email poisons your brain.

But here’s the most important thing: Read a lot of good books while you’re writing. Think about what Gabriel Garcia Marquez called their “secret carpentry,” the tricks the writer used to put them together. Steal all their best techniques. Don’t steal their words—I’m not talking about plagiarism—but steal their methods, their ways of structuring a story. That’s what helped me the most.

Wonderful interview! Annia is an inspiration to me! Yes, her stories will stay with me always! Thanks so much for asking the right questions.

Can’t wait to read this! Sounds like a fabulous book! Thanks for the inspiration, Monica!

i just read this book in two days. what luscious writing. with great appreciation for annia and her skilled creations,

gardenia